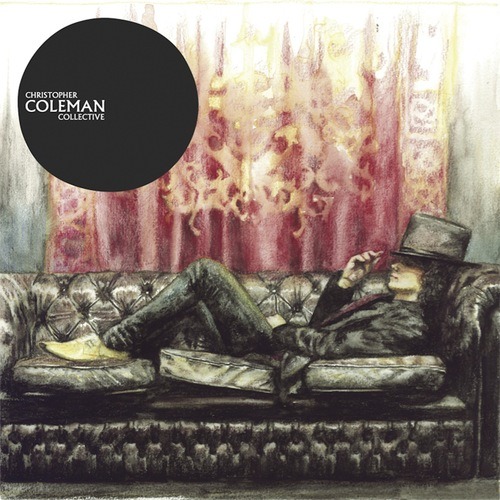

Christopher Coleman is a young musician from Tasmania who records - and usually plays live - with a changeable group of musicians, under the name Christopher Coleman Collective. The Collective has just released its self-titled debut album, and I recently spoke to the very talented man at the centre of it.

Are

you on the road at the moment or are you in Tasmania?

I just got back. We started

over in Port Fairy for the folk festival there and now I'm back for the

Spiegeltent launch in Hobart tomorrow night, yeah. So we've four shows in, 15

to go.

I'm

going to launch into a fairly direct question drawn from your bio, which is how

does a quiet and anxious child go on to become a performer?

[Laughs] I've got no idea.

It's a complete paradox which I haven't the slightest - yeah, the human mind

does curious things, doesn't it?

Well,

your music and your bio actually suggest that you've got quite a passionate

nature so, maybe, I don't know if music is an overriding passion in your life.

Maybe that's how it takes you from being quiet and anxious child to being a

performer?

Yeah, absolutely. It's the

one love, I'd say.

You

grew up in a musical household and - except from - you said that you didn't

start writing songs until you were 16 despite being surrounded by songwriters,

it seems, at home. So I was wondering what might have changed for you around

that age that you decided to start writing songs and, I guess, playing more

because you didn't play much as a child either?

Yeah. I think it was

hormones, really –

[Laughs].

– that prompted me to start

writing. But, yeah, I did get an instrument when I was three or four. It was a

ukulele, and then [I] played the trombone in a primary school band when, I

guess, I was 11. And then when I was about 13, I started tinkering away on my

dad and older brother's guitar. And yeah, by 15 I was ready to write songs

[laughs].

So

just back to what you said about hormones being what made you write – was that

because you were trying to pick up boys or girls or just to express what you

were feeling?

It wasn't a conscious thing.

It was - yeah, I was just sitting at my grandparents’ shack and noodling away

on a guitar and then thought I've got a little vocal melody happening and got a

pen and what came out was my first juvenile love song.

[Laughs].

First of many to come.

Do

you still have that song tucked away somewhere?

I do but it'll never see the

light of day if I have anything to do with it.

It's

part of your archive.

Yeah [laughs]. Yep.

You

mentioned in your bio that in one of the earlier bands you were in, you were

playing old-time happy-go-lucky numbers in nursing homes. And I was wondering

what sort of old-timey songs they were.

It was ‘Side By Side’ and ‘When

the Red, Red Robin’ and ‘Bye, Bye Blackbird’ and ‘What a Wonderful World’, ‘Long

Way to Tipperary’. The wartime songs.

And

are those songs that you were familiar with growing up, or you decided, given

that that was your audience, you would go out and learn them?

It was curious – I guess my

grandmother plays piano and so at Christmas time, after a few bottles of wine

and being drunk, we'd all gather around the piano and just sing out these

songs. So they were kind of etched in the back of my mind and then, I don't

know, me and a friend just decided to try and do something good and make a

living from it at the same time. And that seemed like a really good idea – and

it was, yeah.

Which

is pretty extraordinary, because it's not that easy to make a living playing

live. It's easier to make a living playing covers than originals, at least to

start with, but it's still never easy. And reading about you, I realised that

even though to a lot of people it might seem you were Unearthed on Triple J in

2012, Telstra Road to Discovery in 2013 – you're still very young. But I was looking at how much you'd actually

played and I thought it's never an accident when someone matures at the right

time, as it sounds like you have in your music. You've had a lot of playing

behind you and a lot of different types of audiences. So that was your

university degree, I guess, in music.

Yeah, yeah. It was my ad hoc

apprenticeship, I guess. That and busking on the street and playing with other

singer-songwriters and slowly writing my own tunes at the same time. And then

it just out of a jam, a couple of years ago with a friend who came down from

Sydney. We just called up a recording engineer the next day and decided to

record what we'd done, just flicking through my old notebooks of what I'd

written. And that was the first day of tracking for this album that's coming

out.

Well,

that actually brings me to a question I was going to ask a bit later, which is:

given the fluid membership of the Collective, how did you gather people for the

recording – but it sounds like it might have been an ad hoc process.

It definitely was. It was

whoever was around at the time and whoever was interested in playing and liked

the songs at the time. But, yeah, the recording process would usually be

decided upon a couple of hours before we actually tracked something. As opposed

to an organised rehearsal schedule and planning in advance to go in and record

over X amount of days.

And

in terms of who comes with you on the road, then, as part of the Collective, is

that influenced by who's available or are you nominating who you'd like and

hoping that they're available?

Everyone that I've played

with, I love to play with and it's still very much the same approach: who's up

for it and who's willing to slug it out for a little while.

[Laughs].

Because there isn't a lot of

money and it's a big-time commitment.

It

sounds a bit like you're a ringmaster –which is appropriate, I guess, seeing

that you're playing at the Spiegeltent.

[Laughter] You can say that I

- I'd like to think myself as a peaceful dictator.

A

benign dictator. Every organisation needs a benign dictator, I think.

[Laughs] Yep.

It

seems very much from just the amount you've played, given how youthful you

still are compared to – there are some performers in country music, in

particular, who are in their seventies and eighties, so you're young relative

to them.

Yeah.

But

given the amount that you've played and the different forms your playing takes –

busking and with the Collective in certain types of bands – it seems almost

like you kind of exist on this musical wave and however the opportunities

present themselves to perform, you just take them.

Yes. [It was] very much just

like that from day one. It's become more strategised as the Collective has

become busier and we've kind of got plans a year, a year and a half in advance

now. But certainly the first seven or eight years was just blatant youthful

enthusiasm to take whatever opportunity would come up. And it was extremely

exciting.

To

an extent, though, I think it puts you at odds with most other people in the

world, to live in almost permanent creative flow, which is what it sounds like.

It doesn't necessarily make for a contented existence when you're trying to

interact with other people. So I was wondering if you sometimes find it hard to

find your slot, or whether you've been able to meet people along the way who've

gone with you.

It was funny that out at Port

Fairy this weekend, I had the first feeling possibly ever where I was really a

part of a tribe, if that makes sense. Like all of these people have met over

the years, we're all just gathered in this one space for four days and we could

all just hang out. Peers among peers, and it was a sense of belonging which was

really a great feeling. You know how in most of other workplaces there'll be

the organised Friday night drinks after work. I've never experienced that so much

with music because it's – I don't know. You don't run into each other all that

often.

Unless

you're playing festivals, I guess.

Yeah, yeah. And it's really,

really cool to be at that point now where we are and just to relax over a long

period of time and catch up and console one and other about what's hard or

what's great, and it was a really fun weekend.

So

what, for you, are the hard things and what are the great things?

Well, it goes without saying

that money – music isn't a wise choice if you want to be filthy rich or even to

make a modest living, you need to be really, really successful, or what would

be publicly perceived as really successful, is still only a moderate income.

And also the lifestyle in terms of the highs of performing and that extreme

energy that is transferred on a really good show to the next day at an airport

by yourself waiting for a flight for four hours and then not having much to do

for a couple of months until the next tour cycle comes around – it's very in

your face one minute and then nothing. And trying to get some kind of balance

is difficult and being content in both of those periods.

So

what are the great things?

The great things are the – is

the writing process. It's a great thrill and that's really just thriving and the

pen is doing all of the work and you bring the song to the band and they're

completely on the same level and surprise you with embellishments. And then the

recording process, the little flashes of just working and vibrating really

well. And then performing is one step further in terms of the adrenalin rush,

and so sometimes the shows can just be incredibly life-giving like the best

high you could possibly have.

And

others not?

Yeah. Well, generally the

shows are – you feel all right about them but you feel a little bit deflated.

It's easy to focus in on the things that didn't go as well as you would have

liked, rather than the things that did go well – but, yeah, generally most

shows are kind of ‘yeah, we did all right’, and then there's the odd one that's

just like ‘oh wow, that was really special’, and then an equal amount where

it's just, like, ‘yeah, that was a car crash. It was a disaster.’ [Laughter]

And

I suppose it's never easy to identify what the common elements are for the car

crash ones or the excellent ones?

Yes. It's curious, because

it's the same material that you're playing generally, bar one or two songs you

might bring into change it up a bit. After a while, if you're introducing

songs, they take a similar banter. It's not scripted but it's repeating a

certain show to a certain extent. And so it's funny how sometimes it's just

right and other times it's wrong, but usually it's just in the middle

somewhere.

Just

going back to something you said before about being publicly or what might be publicly

perceived as being successful. I would imagine it's a real challenge for a

songwriter and performer, and someone who is both, to think about wanting to

have a viable career in music, in performance and in releasing records and also

wanting to do just what you want to do creatively. So I was wondering if you

ever feel … not a responsibility and not a pressure but something in the middle

about having to release material and perform material for an audience. Not to

try to please the public so much, but to try to build an audience and whether

that affects what you write and how you perform if that makes sense?

I'm quite a naïve person and

my approach is similar, in that I just hope, but without thinking about it that

if I'm putting out and writing what feels good to me there's going to be

somebody out there who feels the same way, and I just hope that if I love what

I'm doing then somebody else is going to. When you break it all down, Deborah Conway,

an Australian singer-songwriter, said that you really only need 1000 people who

are interested in your stuff who are willing to come to a show whenever you

tour and buy each record. If you release a record each year, a thousand people

– and you do that on a yearly basis. You can carve out a little niche career

and that's all I'm really interested in achieving. Just trying to find your

little community of like-minded listeners, I guess.

And

I think the key to connecting with an audience is also in something else you

said earlier about the pen flying across the page, doing the work itself, which

suggests that you're a storyteller who understands the nature of storytelling,

which is that the stories don't necessarily belong to you. That you're the one

who's communicating them to an audience. The best storytellers are the ones who

have that experience that you've just described, which is the stories come

through you and because you're trusting that process to a great extent, you're

letting the stories tell themselves. They do find an audience.

Yeah, yeah. The songs are so

much stronger when I'm completely overtired and uninhibited. Then when it's,

like, ‘all right, this week I'm going to try and get down to the piano at 9 in

the morning and I'm going to write for three hours and then …’ I haven't

mastered the art of the conscientious, focused writer. I'm still in that

youthful, completely reliant on the muse [phase], I suppose.

I've

actually only ever interviewed one singer-songwriter – and I've now talked to a lot of them – who

turned up every day at the studio and wrote. Everyone else, regardless of age,

seems to wait for the muse to strike or the flow to kick in or however you want

to describe it.

Yeah. Right.

The

one person who did do it every day said that she did that because she said you

have to write the bad songs in order to get to the good songs and that was her

process.

I agree with that but I just

can't seem to do it. But that's the thing – the people that I really look up

to, like your Nick Cave or Paul Kelly, Leonard Cohen, they've all said that

they get down there and even ABBA all turned up to work and did varying levels

of how hard they pushed it. But, yeah, I think you need to be ready it all

times at least to honour when the muse does strike, I guess.

Except

Benny and Björn from ABBA used to go to their nice little cottage on an island

off Stockholm to write.

[Laughter] They wrote some

great songs.

They

absolutely did. They were also control freaks in the studio, by the sound of it

[laughs].

Yeah.

Now,

I'm curious that you went into Telstra Road to Discovery, because it used to be

Telstra Road to Tamworth. It's not that any more. But it's quite a structured

talent quest, for lack of a better descriptor – the structure of it seems to be

slightly at odds with what seems to be the fluid nature of your work usually.

So how did you find being in Telstra Road to Discovery?

It was completely bizarre and

you picked it well in – it didn't come naturally to me, but I'm so glad that I

did do it because it was just a whole new community of people to bounce ideas

off and some of my really closest friends were a part of that. And there's no

doubt that the program has led to some really great opportunities for my music

and they're really genuinely supportive of emerging independent artists, [and]

I don't know of any other massive corporation doing that. I'm sure they've got

their reasons to do it but it was so much more of a pleasure than I expected it

to be.

Well,

that's fantastic. And I've got to say from my perspective, as someone who now

has a lot about the Australian country music industry in particular, the

country music audience is extremely receptive of new artists regardless of age

or sex or even the sub-genre of country music therein. And I think because it

was originally the Road to Tamworth, Telstra knew that they could take young

artists and get them out to an audience and the audience would be receptive.

And I think that hasn't changed, even though it's no longer just focused on

country music. Country music to me is an anomaly, really, culturally speaking,

in all sorts of ways, because it seems to be the only form of Australian

culture – including books and films – where there's an audience just wanting

and accepting new artists. It's really fantastic.

Absolutely.

So

there you go, that's my little spiel about country music [laughs].

I couldn't agree more. I had

my first experience at Tamworth earlier this year and it was very much what you

were describing.

I'll

just ask you one more question, because I realise time is ticking away. Your

album is an independent release, as a lot of albums these days are. I'm

starting to wonder if record companies will have anyone left to put out. And I

was wondering if you like having your independence or has it been more work

than you expected?

No. I'm really glad, I'm so

glad that it's independent. I'm very lucky to have got a team around me to help

all of the logistical and business sides of the process. I don't think that I

could - I certainly couldn't have done it all myself. But yeah, I imagine that

all of my releases will remain independent.

I

think it's a really interesting time actually, in Australian music, at least. I

don't know what's happening elsewhere but I'm seeing such great quality

recordings, including yours, as independent releases and the artists owning

their own material, owning their own recordings which never used to be the case

and putting out beautiful-looking CDs and the quality of the production is

fantastic. So it's a fascinating time really.

Yeah. It's really open for

every man and his dog and that's a really good thing.

Before

I close, I'm just going to say when I was first listening to your record I

thought it was going someplace and then it went absolutely another, and it was

a really beautiful revelation when it went into these other places. And I think

that's probably the way your music and career will continue to go, heading in

one direction, going to another but the results will always be great.

That's kind, thank you.

No comments:

Post a Comment